Slowly, the Eastern Dream picks up speed and as we are gliding out of the harbor Vladivostok's spectacular setting on steep hills and the beautiful Golden Horn Bay offer magnificent views. Our Russian adventure is over and we are on our way to Japan. Suddenly, we pass floating ice floes and a moment later, the ship is surrounded by ice. Here, the Pacific Ocean is frozen and it feels as if we are embarking on a journey to the Arctic. As Vladivostok disappears in the distance, Russky Island comes into view, along with the gigantic Russky Bridge, the world's longest cable-stayed bridge. We are gliding right under it and gazing up at its massive 320 meter high pylons gives me mixed feelings about man's ambitions.

Standing on the deck of the ship and looking at the frozen surface of the Pacific, I am reflecting about our winter journey through Siberia… The images I had of Siberia before this journey were those of a cruel and inhospitable place where political exiles and prisoners of war were sent to die in inhuman conditions. Its reality is different – yes, Siberia is bloody cold in winter but its inhabitants seem to turn the cold into something positive: they enjoy fishing on the frozen rivers, build cozily warm houses, bathe in Banyas, the Russian-style saunas which during cold winter nights turn into social meeting places, and in the towns create beautiful ice sculptures and slides which are a delight for kids.

Most of the Russians we met are very friendly and welcoming. I am thinking about Alexander, our guide at Lake Baikal who shared his house and self-made vodka with us. In Ulan Ude, we stayed at the home of Olga, a charming elderly lady. Our conversations with her in her lovingly decorated apartment inside a grey Soviet era apartment block let us glimpse into everyday life in Russia. When we asked her about how she copes with the cold, she responded "yes, the cold is sometimes hard, but people here are used to it and most of us can't imagine living anywhere else".

But of course, Siberia has less pleasant sides as well. Crumbling Soviet time buildings and factories litter the outskirts of towns and there is incredible pollution, visible especially in the early mornings when against the morning sun fumes from industrial plants, houses and vehicles look like a hellish fantasy straight from Dante's Inferno. Alcoholism seems to be a major problem in Siberia - drunken men often stagger on the side of the roads, not unlike to Kenya. One Sunday afternoon we ask a woman in a small village for directions and are shocked when in response she clambers into the back of Pele being visibly drunk. Getting drunk in Siberia can be life threatening – one night, we found a man lying unconscious in the snow at -35°C. He was so drunk that he didn't even respond when we repeatedly shook him to wake him up. Eventually, we took him to a nearby restaurant and called an ambulance. I have no idea whether he would have survived the night outside.

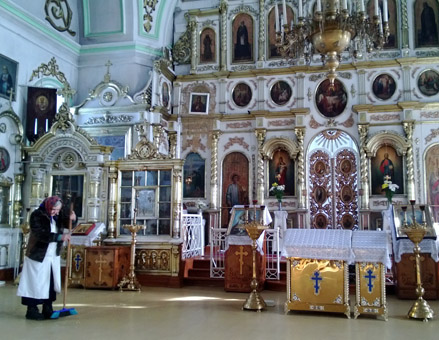

On the other hand, religion appears to play an important role in Russia in spite of more than 60 years of Communism and atheist rule. I was surprised by the deep piousness displayed in churches. One Sunday, I attended an orthodox service – throughout the service, the congregation stood in front of the altar where a ceremoniously dressed priest swung a golden metal censer suspended from chains in which incense was burned. In a small village church, I felt touched by an old woman shuffling about as she was cleaning the church floor with a broom, every now and then stopping and saying a prayer in silence.

These are the thoughts going through my mind as I see Siberia disappear in the mist over the Pacific Ocean. It is getting very cold and I decide to go inside where legions of mainly Russian and Korean passengers turn the Eastern Dream into a happening place. They exhibit distinctive behaviors. The Russians huddle in quiet corners for a picnic with vodka while the Koreans seem to be determined to make this journey the best time of their lives. Later that night, they congregate in the discotheque and never before have I seen Karaoke being celebrated with such passion – middle aged and elderly Koreans sing with full emotions while their audience is getting into the groove, cheering like teenagers and making me feel like being in a pop concert.

These are the thoughts going through my mind as I see Siberia disappear in the mist over the Pacific Ocean. It is getting very cold and I decide to go inside where legions of mainly Russian and Korean passengers turn the Eastern Dream into a happening place. They exhibit distinctive behaviors. The Russians huddle in quiet corners for a picnic with vodka while the Koreans seem to be determined to make this journey the best time of their lives. Later that night, they congregate in the discotheque and never before have I seen Karaoke being celebrated with such passion – middle aged and elderly Koreans sing with full emotions while their audience is getting into the groove, cheering like teenagers and making me feel like being in a pop concert.

The next morning, I visit Pele in the cargo deck and am happy to see him covered in the flags of the 12 countries we have travelled so far. He has been doing great, and we only had to do routine services and relatively minor repairs, in spite of us not always treating him well. Twice, we have driven him into snowy ditches and he had to be pulled out by other cars. When arriving in Ulaan Baatar, Mongolia's capital, I forgot that the hand brake didn't work and left Pele parked in neutral gear. As I was walking away, I suddenly heard cars honking and people screaming and looking back, I saw Pele rolling backwards onto the road. Two drivers narrowly managed to avoid a collision but a third was less lucky and Pele hit the front of his car. Quite perplexed and shocked, the driver came out, and I realized that of all cars, Pele had selected a Buddhist monk's vehicle as his target. I deeply apologized to the monk, and in the spirit of Bhuddism we quickly found an amicable solution to the situation. Pele didn't even take away a scratch from this incident!

The following day, we arrive at Sakaiminato port in Western Japan and I drive Pele out of the ship onto the quay. The ferry representative informs that I am not officially allowed to drive on Japanese roads as Kenya hasn't signed some International Convention on Driving Licenses. This brings us into an unexpected predicament – it is Friday and we only have until Monday morning to reach Yokohama and the container vessel that is supposed to take Pele to the US. I am also told me with a hushed voice that only few policemen are aware of this restriction and I might therefore try to drive Pele anyway. The only alternative would be to put Pele onto the back of a truck and have him transported to Yokohama. This, however, would be very expensive and somehow seems to violate the unwritten ethics of a road journey. Therefore, we decide to take the risk and embark on the 800 km drive crossing Japan from West to East, hoping that we won't be caught by Japanese police…